Adventist Peace Radio, Episode 36: Adventism & the FBI in WWI

Kevin Burton describes how the FBI investigated and influenced Adventism during WWI.

Read MoreKevin Burton describes how the FBI investigated and influenced Adventism during WWI.

Read MoreDivisions in the world and in religious circles call for reflection.

Read MoreWhen drafted, James Wagner followed his convictions regarding killing and observing the Sabbath. What would I do?

Read MoreWhen remember the end of WWI, we also remember those who refused to kill.

Read MoreIn commemoration of the one hundredth anniversary of the end of the First World War the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Germany adopted the declaration "The Audacity of Peacemaking" ("Mut zum Frieden"). It was published in the February 2018 issue of the church magazine "Adventisten heute". In the statement the leadership of the Adventist Church recommends its members not to participate directly or indirectly in a war.

Read More

Reinder Bruinsma originally posted this essay on his blog (30 October 2014, link). Dr. Bruinsma was one of the presenters at the WWI symposium APF reported about this summer (link), and he is contributing two chapters to a book on Adventist mission and social ethics that will be published by the Andrews University Press in 2015. See his full (translated) bio below.

Flanders Field

It was some twenty years ago that I first realized how terrible the First World War had been. In far away Australia I visited the War Memorial—a museum that pays a lot of attention to the Australian contribution to the Allied cause in the Great War (as WW I is referred to in many countries). During that visit I understood better than ever before that nations from all over the world were involved in this world-wide dispute. A few years ago I was, quite unexpectedly, also confronted with this same fact, as I was travelling with a group in Turkey. Our guide told us that near the Dardanelles more than one million soldiers lost their lives in Word War I.

There are, however, few places that are so moving, as far as the Great War is concerned, as Ieper in Belgium. In a part of southwestern Belgium and the North-West of France one finds dozens of war cemeteries, where hundreds of thousands of men and women from dozens of different nations have found their last resting place. The remains of the trenches in which the opposing armies were involved in an inhuman process of cruelty and senseless violence, still tell their macabre story. But it is, in particular, the Flanders Field Museum in Ieper that is unforgettable in its sadness. It is truly a fitting monument for the millions who lost their lives between 1914 and 1918. And, why and for what, in fact, did they die? Its subject matter would make the visitor even more downhearted, were it not for the magnificent medieval building, the famous Lakenhal, in which this museum is housed.

I have always loathed everything that has to do with war. As a boy I never liked books about war and I did not go to war movies. I was fortunate enough that I could escape the obligatory military service, since I studied theology—which at the time in the Netherlands provided a possibility to stay out of the army. But, had I been conscripted, I would have refused to bear arms. It always made me proud to belong to a church that was opposed to war and that advocated a non-combatant position.

To my deep regret, in many countries this Adventist tradition of non-violence has been watered down, or even changed into the opposite. This is especially true for Adventists in the United States, where so-called patriotic feelings have ‘inspired’ ever more men and women to serve their country by opting for a career in the military. A visit to Flanders Fields should be required for all fellow-believers who consider joining the army!

Yes, I know there are weighty arguments against radical pacifism. I must admit that I am happy that people are currently fighting the IS, and I would not want to live in a place where there is no police. But there are at least as solid arguments for resurrecting the Adventist tradition of non-violence. After all, in our world there are plenty of men and women who are prepared to take up arms. But there are always too few people who want to do everything to promote and model peace. Remember: Blessed are the peace makers. Real happiness is for those who pursue reconciliation and peace. They will be called children of God (Matthew 5:9). My visit to the Flanders Field Museum reinforced in me that long-held conviction.

- - -

Reinder Bruinsma Bio (partially translated by Google Translate; original): "I live with my wife Aafje in Zeewolde (Flevopolder, Netherlands). I have over forty years of experience working within the Seventh-day Adventist Church in various capacities and in various countries. I have written twenty books and hundreds of articles in both Dutch and English. Writing is now one of my main activities. Since September 2011, I also temporarily held the position of president of the denomination in Belgium and Luxembourg. Fortunately, there still remains some time for travel and other fun things.

Featured Image Credit--Flanders Field: By King, W. L. (William Lester) (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2007663169/) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Nathan Brown originally wrote this essay for Adventist World (8 November 2014, link).

Making Peace

November 11 is known in various parts of the world as Armstice Day, Remembrance Day, or Veterans Day. It marks the anniversary of the end of World War I, ironically tagged as “The War to End Wars.”

Sadly, almost 100 years later, we still live in a violent, war-ravaged, and divided world. Violent conflict is a significant cause of injustice, poverty, and suffering. Included in the costs of war are the direct victims and shattered lives, the attention and resources devoted to military machinery that would be better diverted to alleviating other human needs, and the continuing suffering of war survivors and veterans, even among the “victors.”

There is something about making war that messes with our humanity. The ongoing struggles experienced by veterans of the Vietnam War are perhaps the most notorious example of this. Australians were involved in the Vietnam War between 1962 and 1973, during which time 521 Australian personnel died in active service. In the three following decades, 421 “surviving” veterans are known to have committed suicide, with the suicide rate increasing decade by decade.

The figures are even more disturbing when we look at the much larger veteran population in the United States. Reports vary across the many studies that have been conducted, but as early as 1979 a report from the University of Denver’s School of Professional Psychology concluded that “more Vietnam veterans have died since the war by their own hand than were actually killed in Vietnam.”

And the suicide statistics are simply the most extreme count of larger problems, often grouped under the generic designation of post-traumatic stress disorder. Suicide is an expression of the mental, emotional, and spiritual scarring that also contributes to mental illness, homelessness, alcoholism and other drug dependencies, family breakdown, and continuing physical ill-health.

Both in practice and in aftermath, there is a stark difference between being prepared to die for one’s beliefs, family, or nation—“Greater love hath no man than this . . .” (see John 15:13)—and killing for one’s beliefs, family, or nation. That is why the people of God are called to a different way of living, even amid the violence, warmongering, and other conflicts of our world. The kingdom of God, as inaugurated by Jesus, is never advanced by violence.

At the heart of the gospel of Jesus is God’s gracious and grand act of peacemaking, reconciling sinful human beings with their Creator. This is another way of understanding the plan of salvation, and one that we can readily appreciate from our experiences of human relationships. And the reconciliation we receive becomes the pattern for us to be “ambassadors” for this reconciliation (see 2 Cor. 5:18–21).

Even in the Old Testament, the concept of peace is closely linked with salvation and the gospel: “How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news of peace and salvation” (Isa. 52:7, NLT*).

This gospel of peace also becomes the motivation, pattern, and resource for working for peace in our violent world: “The heart that is in harmony with God is a partaker of the peace of heaven and will diffuse its blessed influence on all around. The spirit of peace will rest like dew upon hearts weary and troubled with worldly strife” (Ellen White, Thoughts from the Mount of Blessing, p. 28).

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said, “God blesses those who work for peace, for they will be called the children of God” (Matt. 5:9, NLT). Taking this further, not only did He affirm the commandment against killing, precluding Christian support of war, He said we should not be angry or hold a grudge (see Matt. 5:21-26), and that we should love our enemies and pray for those who persecute (see Matt. 5:43-48), meaning that we should take active steps to seek their good.

There are many inspiring stories of people who have devoted their lives to peacemaking in world trouble spots, bringing glimpses of reconciliation and healing, and often alleviating much of the injustice and suffering these conflicts have brought. Whether working for peace between nations or between two bitter family members, Jesus said that those who do such work will be rightly described as “children of God.”

*Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.

Featured Image Description & Credit: "Box with graves of deceased internees of several conflicts at the Bremgarten cemetery in Berne; Berne, Switzerland. In the foreground polish in the background french and belgium soldiers (1914–18, 1939–45), in centre the stele for the deceased internees of the armée de l'est (1871), WWI and WWII." © Chriusha (Хрюша) / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / (optional) Wikimedia Commons.

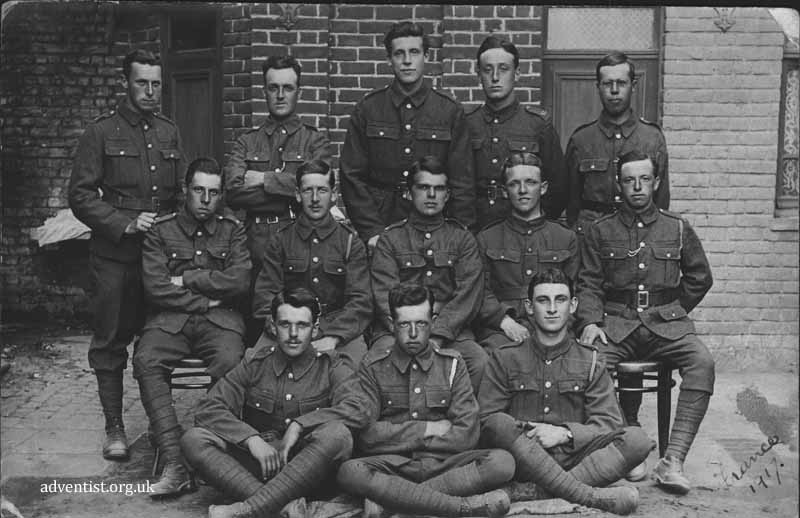

The Adventist Review continues the recent focus on the anniversary of World War I with the story, "14 Soldiers in God’s Army" (Victor Hulbert, 28 Oct 2014).

The article begins with a brief description of the abuse the Adventists experienced:

Fourteen Adventist soldiers laid down their tools at 4:00 p.m. on Friday to prepare for Sabbath. But the sergeants were ready, armed with sticks, revolvers, and boots. Severe beatings followed. The bruised British conscripts then were roughly thrust into prison cells, irons tightly clamped on their wrists, digging into their flesh, their hands behind their backs.

After relating the staggering statistics relating to WWI, Hulbert shares,

Adventist soldiers found a different kind of horror. Determined to keep the Sabbath and not carry weapons, they were beaten, starved, forced to clean toilets to a shine without equipment, and punished with the dreaded “crucifixion,” which saw soldiers shackled in irons and painfully strapped to a gun wheel or some other object for hours in the hot sun.

Hulbert describes the difference between the ways leaders in Great Britain and Germany responded to the war. Adventists in Germany predominantly supported fighting for the nation, though some did resist, which led to the Reform Movement.

Adventists in Britain took a different stance. They followed the Adventist example of noncombatance adopted during the American Civil War in 1861 to 1865. This was not an easy choice, and British Adventists were widely scorned as belonging to an odd, working-class church exported from the U.S.

Things went smoothly, more-or-less, for the first 18 months for the Adventists who were conscripted.

But a new young officer took charge in November 1917, and he declared that Sabbath duty was mandatory. When the Adventists refused to work, they were placed under court martial and sentenced to six months of hard labor at Military Prison No. 3 in Le Havre.

The lengthy article addresses how the Adventists were treated in prison and the steps to their eventual release. Special focus is given to their first Sabbath in prison.

The complete article can be read here.

Additional APF stories about WWI:

The Seventh-day Adventist Church in the United Kingdom has compiled information regarding how Adventists in the region responded to World War One--WWI and the Adventist Church. "There were roughly 2,500 Seventh-day Adventist members in the UK in 1914. Some 130 of them were conscripted." The men who chose to be noncombatants experienced "scorn, humiliation, arrest, beating, and even threat of death." Furthermore, "a number spent time in Dartmoor, Wakefield or Knutsford prisons. A particular group of 14 were sent to France and following a court martial in November 1917 were sentenced to six months hard labour at Military Prison #3 in Le Harve."

The Seventh-day Adventist Church in the United Kingdom has compiled information regarding how Adventists in the region responded to World War One--WWI and the Adventist Church. "There were roughly 2,500 Seventh-day Adventist members in the UK in 1914. Some 130 of them were conscripted." The men who chose to be noncombatants experienced "scorn, humiliation, arrest, beating, and even threat of death." Furthermore, "a number spent time in Dartmoor, Wakefield or Knutsford prisons. A particular group of 14 were sent to France and following a court martial in November 1917 were sentenced to six months hard labour at Military Prison #3 in Le Harve."

In addition to four PDF documents--WWI Brian Phillips, Adventist Heroes Devotional Talk, Armstrong Letter 1957, The Tribunal 4-04-1918--the website also lists a number of primary sources and links for further study.

The site also has a devotional video from the 2014 SEC camp meeting. The speaker in the video is "Victor Hulbert, great-nephew of Willie Till, one of the 14 who were court martialled and imprisoned in Le Harve."

Finally, a trailer for the film, A Matter of Conscience, is provided. The complete film is now available:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qSLHb0TGcQ?rel=0&w=560&h=315]